Mary Pat: For the past 7 months, I’ve had the great pleasure of working as Interim Director of Coding for Marta de la Torre at Steward Medical Group, a mega group of 700 physicians and mid-level providers associated with 12 hospitals in Eastern Massachusetts. I greatly appreciate her willingness to share her fascinating story about working Abu Dhabi for two years as a Revenue Cycle Director.

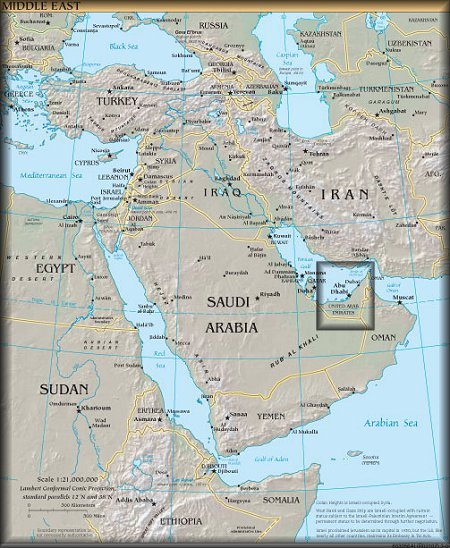

NOTE: The United Arab Emirates, sometimes simply called the Emirates or the UAE, is an Arab country in the southeast of the Arabian Peninsula on the Persian Gulf, bordering Oman to the east and Saudi Arabia to the south, as well as sharing sea borders with Qatar and Iran. The UAE is a federation of seven emirates (equivalent to principalities), each governed by a hereditary emir, with a single national president. The constituent emirates are Abu Dhabi, Ajman, Dubai, Fujairah, Ras al-Khaimah, Sharjah, and Umm al-Quwain. The capital is Abu Dhabi, which is also the state’s center of political, industrial, and cultural activities. Of note, the native Emiratis are outnumbered in their own country at a ratio of 11 to 1. Emiratis now make up only 9% of the population and expatriates make up the remaining 91%.

Mary Pat: How did you learn of the position in Abu Dhabi?

Marta: I got a cold call from a recruiter. It came at a point in my life when I had reached the top of my career with the hospital I had been with for 13 years. I did some research and found out that for an Arab country, Abu Dhabi was a much more westernized country than Saudi Arabia, Qatar or Bahrain. What excited me most about working in Abu Dhabi was the chance to get in on the ground floor of building a 3rd-party payer system. Having lived through the dysfunction of the American healthcare system, I felt I could bring that experience to Abu Dhabi and help them avoid a lot of the pitfalls the American system has experienced.

Mary Pat: What was the recruitment/hiring process?

Marta: First, I had a video conference interview with the recruiter. Abu Dhabi is 9 hours ahead of the West Coast, so the interview was at 5:30 a.m. one morning. After the interview, I had to answer questions in writing – questions about my management philosophy, problem-solving, and technical questions on areas I would be responsible for. The answers were sent to management team of Sheikh Khalifa Medical City (SKMC) which is the flagship hospital named after the current Sheikh (pronounced “Shake”.) The next step was a video conference with with the Cleveland Clinic team – the CEO, CFO, and CHRO – whom I would be working with in Abu Dhabi.

The entire recruiting process took about 7 months. I was subjected to a very vigorous security check and had to produce my birth certificate, my children’s birth certificates, my marriage certificate, the addresses of my homes for last 7 years and all my school transcripts (don’t EVER throw away your high school diploma!) certifications and licenses. I was asked about my religion, my ethnic background and my gender.

Mary Pat: Did you have to negotiate a contract?

Marta: My contract was with the UAE (United Arab Emirates) government so I did a lot of research online about negotiating contracts for these type of overseas jobs. One of the basic benefits was an annual paid 30-day vacation with round trip tickets to return home. Our apartment and utilities were paid for, and we got an allowance to either bring our furniture over from America or to purchase new furniture once we arrived in Abu Dhabi. My cell phone and internet service was covered and I also had a car and driver. There are no taxes there, so I received a generous compensation with no deductions.

Mary Pat: As a woman, did you have any restrictions on things you could do?

Marta: In Abu Dhabi, the husband always has ultimate say. Even though I was the one who held the contract and was making the money, my husband was the one who was in charge. I couldn’t rent a car or an apartment without his signature. Expatriate women can move about the country freely without a male escort and are not required to wear the abaya (black robe and veil), but we did need to dress conservatively. Skirts must be below the knees, tops must have sleeves past the elbows and there was no plunging necklines, and no shorts.

The government reserves the right to stop you and demand to see your papers. At all times, you are required to carry copies of your passport (which the government keeps for your first 30 days there) and visa, your sponsor letter, alcohol ID card, and separate ID with photo which means you are “registered.” Registration was required before we could open a bank account, get health care or get a driver’s license. The sponsor letter is the letter from your employer that says what you are doing in the UAE and it also states how much money you make. Everyone knows how much everyone makes – salary is not a secret. If you are a non-Muslim, you can spend up to 1% of your monthly salary on alcohol, but you must have an alcohol ID.

Mary Pat: What were your living arrangements?

Marta: We were required to live in hospital housing for 3 months then we could choose to stay there or lease our own “flat”. The way you lease a flat in Abu Dhabi is that you tell the leasing agent what you want and based on your income, several choices are offered. The flats had modern living amenities. We had the air conditioning on 24/7 – the temperature could be 120 degrees outside and we would keep it at 73 degrees inside. There was no dishwasher because most people had maids – there were living quarters for maids in all the flats. You could negotiate a maid in your contract; most maids live with you full-time and might get one day off a month. The maids (and all workers in Abu Dhabi) come from countries such as Sudan, Bangladesh, Ethiopia, and the Philippines. Maids make $50-$75 month, but we chose to have a cleaning lady come in every week. We paid 30 dirhams ($10.00/week) for her to clean 5 hours and do the ironing.

Mary Pat: What was your social life like?

Marta: Eating is the biggest social activity there. In Abu Dhabi, you can get food from every country in the world. The work week is Sunday through Thursday, so Friday starts the weekend and the custom is to get a table in a restaurant for the entire day. You eat and talk all day with friends! There was an American Club with large buffets and alcohol available. Alcohol is not served in any restaurants except international hotels and the clubs.

The shopping was amazing! Because there is so much money in Abu Dhabi, there is a lot of high-end shopping. There is no singing or dancing, no cards or gambling. There were movies to see, English movies that were dubbed in Arabic with English subtitles, Bollywood movies and Arab movies. The newest titles were about 6 months old.

In the winters (average 75 degrees), people will go to the beach for water sports, will go “dune bashing” which is riding ATV vehicles, and will camp in the desert. You can go to resort hotels for the weekend and get reasonably-priced spa treatments and food. It is typical for expatriates to leave the UAE every 3 months for up to a week to travel to other countries for a “sanity break.” Paris is five hours away, it is six hours to London or Moscow and many people went to Africa on safaris.

Mary Pat: Was your work life similar to that in the US?

Marta: In many ways, it was the same. The daytime hours are about the same, but there is a call to prayer for Muslims 5 times a day. Men are required to go to a prayer room (there is one in every public building) or a mosque for the call to prayer. Each call to prayer lasts 15-20 minutes and because it is based on the lunar calendar, the times are different every day. Women are allowed to pray at home and women at work who desire to pray may go to a vacant room and pray, but women are not required to go to a mosque and pray as men are. Employees take about an hour for lunch daily.

I was met every morning with a fresh cup of traditional coffee (with cardamom) on my desk. The Tea Boy, who prepares the drinks for the floor, has a very prestigious job and is looked up to by other employees as he wears a uniform of blue pants and a white shirt. The Tea Boy is responsible for making sure that everyone has tea, water (bottled) or coffee, as you come in the morning and he circles around the floor throughout the day offering beverages to the 75 employees on that floor. If there was a gathering of people or a meeting, the Tea Boy was summoned for beverages. If sweets were brought in, he shared them around, and also ran errands and brought the mail.

Mary Pat: What is the healthcare situation like in Abu Dhabi?

Marta: I worked for Sheikh Khalifa Medical City (SKMC) as the Director of Revenue Cycle for the 500+ bed acute care hospital and 13 primary care and specialty clinics. The government had decided to implement a third-party payer system and 12 months before my arrival in Abu Dhabi they had contracted with a German insurance company to be the plan for the country. They planned to enroll all natives (Emiratis) and give them health insurance cards. Daman (meaning health in Arabic) was the name of the plan. Prior to Daman, the government paid for 100% of all health care.

Some of the barriers to implementing the plan were:

- Patient Access/Registration staff were from third world countries and spoke very little English. Staff would memorize where each piece of information should be entered as opposed to reading the field names to determine what information went where. After a software upgrade, staff continued to enter information in the same fields, even though the required data for the fields had changed. We had to start all over teaching the patient access staff how to complete the screens. I had no idea when I accepted the job that we would have to start over from the beginning and rebuild the revenue cycle from the ground up.

- Patient Access/Registration staff had to ask patients for their Daman card, which were originally printed in German (!), but many Emiratis did not realize they were supposed to keep the card or present it when they went for healthcare services.

- The Daman cards had pictures of the beneficiary, but women were pictured in their abayas (with only their eyes uncovered) and men were pictured in their “khandura” white headgear, so low resolution cameras made all photos look almost the same.

- Daman required that beneficiaries pay the equivalent of $8 as a co-pay, but collecting that co=pay was fraught with danger as it was not customary for workers to ask Emiratis for money.

- Most physicians were from single-payer countries using ICD-10, so being required to use ICD-9 was a mystery to them. They didn’t understand CPT, RVUs or any type of reimbursement system.

- English ICD-9s and CPTs had to be translated into Arabic for services to be paid.

Other interesting customs in Abu Dhabi:

- Entire families come to the hospital and live in the room with the patient, helping to take care of them. The hospital rooms are huge to accommodate families, who bring rugs and cooking utensils to cook for the family and patient while in the hospital. Cooking in the hospital rooms is not okay with hospital, but they can’t stop it.

- Inpatients are expected to be in the hospital for a long period of time as there are no Skilled Nursing Facilities (SNFs) or Long Term Acute Care Facilities (LTACs). Patients are discharged to their homes and they have to be well enough to live at home.

- Hospitals must maintain a wing at all times in complete readiness for the Royal Family in case any member needs care. Regardless of whether or not a member of the Royal Family is in residence, a dedicated doctor and nurse are always available, as is fresh coffee, food and fruit.

Some of the improvements I was able to accomplish were:

- We implemented best practices from the US starting with basic processes, as Daman denied 97% of claims due to GIGO (Garbage In Garbage Out) at the beginning. We taught people how to read the screens and used visual aids to overcome the language barriers.

- We used Patient Experience Officers, which were Emiratis there to help patients understand the system.

- We taught the use of of ICD-9 and CPT codes.

- We implemented case management, a Clinical Documentation Improvement (CDI) program and a program for nurses to help doctors document their care.

- We collaborated with social workers and doctors to develop transition programs for patients returning to their home countries, and discharge planning for those expatriates without families who were staying in the country.

- We implemented wRVUs (work Relative Value Units) to measure physician productivity.

I wish I could have accomplished more while I was there, but I am happy with what our team did together.

Mary Pat: Were there language barriers?

Marta: English is the business language of the country, and most people speak English so communicating was not too much of a problem. For shopping, there were souks (traditional shops) for spices out of the bag and for fruit, but there were also American-style shops. One British market, Spinneys, had a pork section behind closed doors away from other food.

Mary Pat: Were there technology barriers?

Marta: The internet is censored so you cannot say anything you want to on the internet, and Blackberry phone service is hosted by the government so it is also censored. We could get Fox News, the BBC, and many more foreign stations, as well as Al Jazeera English, an independent broadcaster owned by Qatar whose motto is “The opinion and the other opinion.”

Mary Pat: What did you miss the most in the US?

Marta: I missed the celebrations, the holiday seasons and I missed my family. It took 24 hrs to go the 13,000 miles to go home. I worried that if there was a crisis in my family, it would take a long time to get home. Most of all, I missed being around people who spoke the same language, were familiar with my customs and where I felt I fit in. I always felt out of place in Abu Dhabi; I never felt accepted.

Mary Pat: What do you wish had been different about the experience?

Marta: I wish they had assigned someone to us who had been there for awhile to help us assimilate, which would have eased the shock considerably. When we arrived, we were taken to the hospital housing with no food, no towels, and only American money to use to buy the immediate necessities. Everyone that had come before me was from Cleveland Clinic and had that built-in support. I was one of the very first non-Cleveland Clinic employees.

Mary Pat: Would you recommend others to take positions in Abu Dhabi?

Marta: It’s quite hard for a woman if you are in a position of authority, and if your spouse is the employee, there’s not a lot for you to do, mostly shopping. People stay inside during the day and come out at night. There was a pediatric shot clinic that opened at 11pm and closed at 3am.

I look at America with a new set of eyes and appreciate the freedoms I have. I can hold any position I am capable of holding. I choose what I wear. I can choose whom to associate with and whom I can eat with – there are no class barriers. I think more about how I can give back to others and less about material things.

Marta de la Torre can be reached at marta.delatorre@steward.org.